Houston and the Gulf Coast of Texas have possibly the largest concentration of petro-chemical facilities in the USA. Of the 150 refineries in the US, 26 of them are located in the greater Houston vicinity, and an additional 28 are located outside of Texas, but still on the Gulf Coast. With the approach of Hurricane Ike, America, knowingly or not, quaked at the thought of this uncontrollable threat to its petrol supply like a junkie watching his dealer be arrested. Ironically, our petrol use is what causes the very threat that can so easily disrupt our supply.

Having been to Houston to photograph the industry in 2006, I wanted to go back and see the result of Ike on the industries and surrounding communities. The Parras Family is involved with various environmental groups that focus on the environmental and health impact on minority groups, and they generously offered to put me up. Alas, I had no time to stay in Houston and visit, as I was off to Brazil the next day, so the only option was to fly down, do the shoot and come back in less than 24 hours. Of course, my flight was delayed, yet Brian Parras of Clean patiently met me for my late-night arrival at the airport.

We made it back to Brian’s house, albeit after midnight, where we met Brian’s father, Juan. Unfortunately, Juan, a relentless defender of the environmental rights of immigrant groups with whom I had communicated for years, could not stay up to chat with Brian and me, so after a beer and a bit of conversation, Brian, Leandra (his girlfriend) and I retired in anticipation of our 5 A.M. wake-up call.

A few short hours later, Brian and I were barely awake and stumbling towards his car, off to meet our pilot, Eric Hake, who stepped in to fill the void after our first pilot backed out, literally as I was on the commercial flight from New York.

A few short hours later, Brian and I were barely awake and stumbling towards his car, off to meet our pilot, Eric Hake, who stepped in to fill the void after our first pilot backed out, literally as I was on the commercial flight from New York.After the media buildup of the storm and its aftermath, I expected to find a devastated city surrounded by a petro-chemical industry overturned and in disarray. My experience is that the media tends to exaggerate any event to such an extreme that it is dubbed the "event of the century." What I found around Houston was a place that had been hit by a bad storm. My interest is environmentally harmful industry, and I did find tanks partially shredded (though mostly older ones, already rusted), and in particular, the demolished cooling fan unit of a power plant, but largely, industry was back in business. There were plants with flaming stacks pouring acrid smoke into the wind streams going straight to Houston, and bulldozers moving material back and forth into the holds of waiting ships, but all of that is expected. What was interesting were the locations where I remembered piles of dry material (like sulphur) that were no longer, and tanks of liquid waste once full were now empty.

One would expect that high winds would blow away any uncontained dry material or open bowls of liquid; the question then arises: where did it go? Once blown away, these materials quickly “disappear” into the surroundings, though dissipate is more descriptive, yet the effects linger for years. The environs and neighborhoods bordering Houston’s petro-chemical industry have long suffered the brunt of their discharge, and this instance was no different. Reports have come in of offshore rigs destroyed, massive spills from offshore sources, as well as tremendous leaks and spills within the industrial area. Here is an interesting article from the Houston Chronicle.

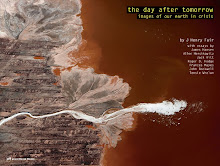

The bottom line is, with climate change predictions and increased storm activity and the fact that most of our refineries on which our society depends for its function are in coastal areas with high probability of this storm activity, there is a dual threat to our environment and security. This Houston trip produced some great images, but not the smoking gun I thought would be uncovered.

I loved this sunken ship; imagine the spill that occurred when it went down...

I loved this sunken ship; imagine the spill that occurred when it went down...